Computer Space released in 1971 by Nolan Bushnell and Ted Dabney is widely considered the first arcade game. While it wasn’t a massive commercial hit, it proved that money could be made from creating video games and the authors went on to found Atari to take the concept to the next level with Pong 1.

It has a unique fiberglass design that aimed to appear futuristic and still makes it look unique to this day compared to the wooden arcade cabinates that followed it.

Despite its name it is not actually a “computer” as microchips were too expensive in 1971 so it used TTL (Transistor-Transistor Logic) which meant that the “code” was actually the series of wires and switches that connected to each other. So to change the functinality or fix a bug it meant actually physically resoldering the connections.

Early arcade games didn’t use a programming language at all with all the game logic built at the hardware level. So to change the game it meant literally rewiring the hardware components and modding involved adding new hardware components which bypassed the original behavior.

As for later arcade games that had a microprocessor the programming language used can depend on the power of the system, some less powerful boards used pure assembly to write the game code and others used a higher level language such as C.

For example the 1990 game Klax was written in C according to Greg Omi who was sent the source code for his Atari Lynx port of the game 2.

This is further confirmed in a 1990 interview with original designer of Klax Mark Stephen Pierce3:

“All Atari coin‑ops today are written in C ‑ that’s the most popular language with the programmers here, I guess. The actual programming work is carried out on standard terminals, and then transferred into our VAX machines where it’s compiled and compressed. Finally it’s downloaded from there through an EPROM burner and onto the hardware for the game that the engineer has put together. Every coin‑op’s hardware is different partly because each game is different, and partly as a form of copy protection.

In the 1990 interview with Mark Stephen Pierce the following was published (in “The One” magazine) 3:

Mark’s graphics are produced on a PC ‑ but using Atari’s own specially written utility: RAD (Rendering and Animation Design). “It’s basically a standard paint tool with some animation facilities. I design and draw on the PC before uploading everything to the VAX to be compressed.”

In the early days of arcade gaming, development teams needed to be highly specialized. Unlike today’s streamlined development environments, both hardware and software had to be built from scratch for each new game. This required expertise across a wide range of disciplines, from custom chip design to game logic and audiovisual presentation.

As arcade hardware evolved and became more standardized—often borrowing from or influencing console architectures—the hardware workload decreased slightly. However, the software and design demands increased, calling for larger, more diverse teams to handle game mechanics, visual design, sound, and player experience.

A great example is Taito’s groundbreaking 1987 arcade title, Darius, which employed a team with clearly defined roles:

For a deeper look into the development of Darius, check out this excellent translated interview on shmuplations:

Darius I & II – 1986/89 Developer Interviews – shmuplations.com

In 1990 Atari developer Mark Stephen Pierce had the following to say about the length of time for developing an Arcade game:

An Atari game takes, on average, around a year to produce ‑ but then an average can come from two extremes, which is certainly in Mark’s case - Escape took over two years to put together, whereas Klax was written in just four months!

The challenge with Arcade games is they are expensive to produce and need to be visually appealing, easy to grasp, and have a carefully balanced difficulty level. Challenging enough to be engaging but not so hard that it drives players away or so easy that it allows endless play on a single coin.

So prototype Arcade games were placed into various arcades and player behaviour was closely monitored to strike the right balance of difficulty and engagement. The Atari games even had a video recorder built in so that the development team could watch how players played the game, along with a computer that tracked the money made for the game 3.

Taito put together a 250-page Hardware Manual for new developers who joined the team to learn how to create an Arcade game from scratch using RAM/ROM/CPU chips and a standard TV. This was before the internet and even before there were many books on the topic when the industry was very new and companies didn’t want to share their “trade secrets”.

With the Taito Hardware Manual for reference, new engineers were sent out to Akihabara to get some ROM and RAM chips and a CPU, solder them all together onto a test PCB, then write a brick breaker game.https://t.co/huXblA0rv4https://t.co/CXlnKUPHkH pic.twitter.com/Yip45KbLIE

— Taito Corporation (@TaitoCorp) January 19, 2024

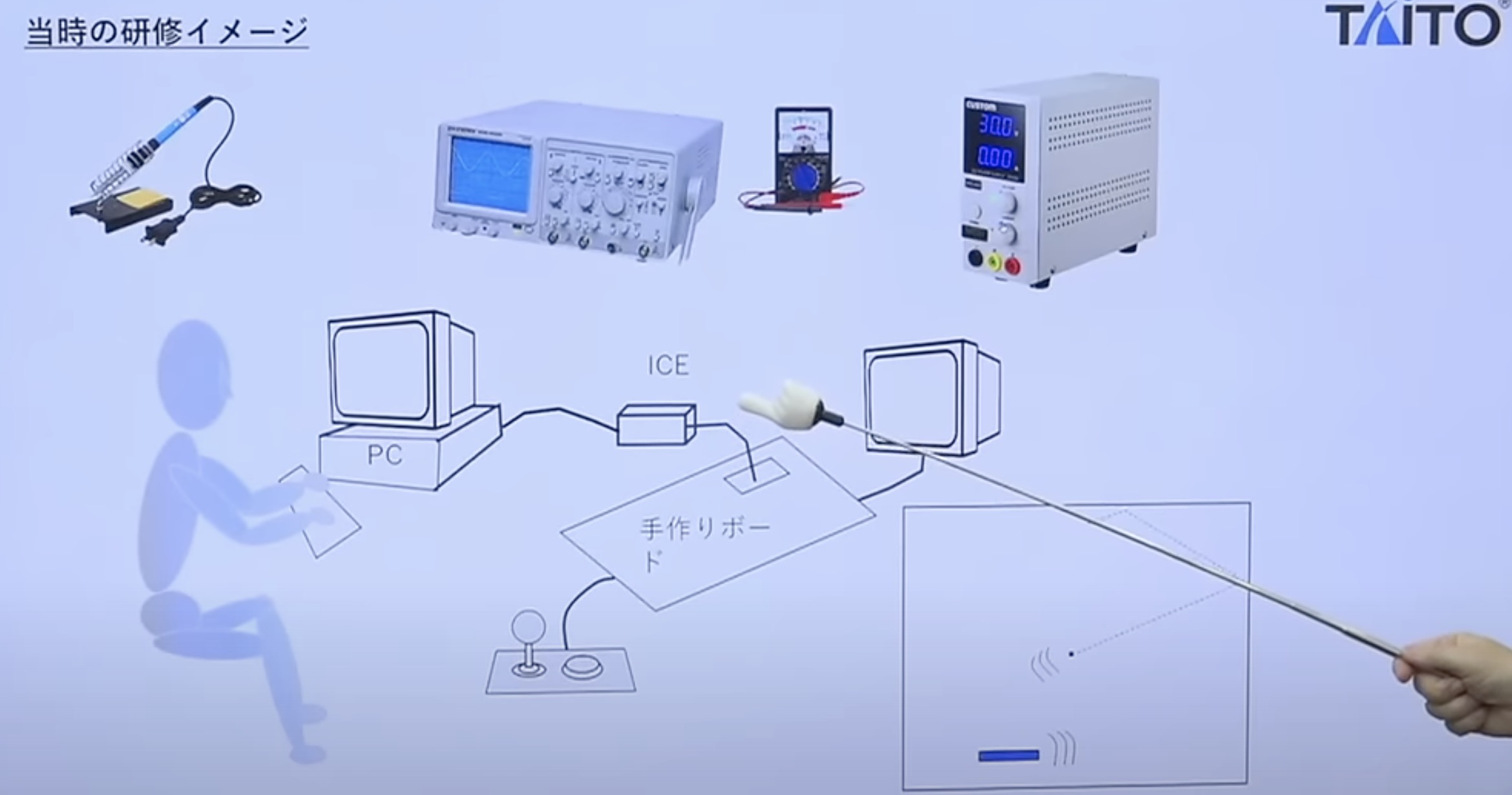

They used an In-Circuit Emulator to debug the programs they were creating as can be seen in this diagram:

At GDC 2014 Eugene Jarvis gives an excellent presentation about the development of Robotron:

They used the Gimix 6809 as their development system:

As for the software side, they had to write their own text editor and assembler, they didn’t comment or use tabs as every byte that was used in memory was precious:

In Retro Gamer 28 there is an excellent article from Archer Maclean where he went to a presentation by Eugene Jarvis and this is what he had to say 4:

He went on to describe that his code spilled over into multiple files on more than one floppy, and yet there were no multi-floppy code-linkers so he devised the exact same bizarre jump vector solution I had devised to allow non-linked blocks of code to communicate. Then he described how he had to write ‘utilities’ to edit tiny bitmaps drawn on graph paper and entered as hex, and how to get around the one hour compile times by editing memory directly and disassembling in your head, and how to make interesting sounds from 30 bytes of data, and how to write ultra-tight optimised machine code to move small bitmaps around a screen fast, and off course, cram it all into a 32k ROM.

The source code for the classic arcade game from 1981 Defender has been released on Github: mwenge/defender: Defender(1981) by Eugene Jarvis and Sam Dicker

It is written in a variant of the Assembly language specifically for the Motorola 6809 CPU 5.

The physical board had 11 ROM chips on it that would need to be flashed with the assembled result of that source code 5.

Defender was developed by Eugene Jarvis and Larry DeMar two programmers who utilized algorithms to great effect rather than relying on artists, one such example is the classic explosion particle effect. Defender became one of the highest grossing arcade games in history 6.

The first issue of the Magazine Wireframe contains a python (pygame) code snippet to re-create the classic particle explosion from Defender 6. You can find that code on github too: https://github.com/Wireframe-Magazine/Wireframe-1/blob/master/explosion.py

Speed-up kits, also known as enhancement kits, were aftermarket hardware modifications designed to alter the behavior of arcade games. These kits typically increased game speed, introduced new features, or adjusted difficulty levels. By modifying the original game code or hardware, speed-up kits aimed to rejuvenate player interest and extend the commercial lifespan of arcade cabinets.

The primary motivations for implementing speed-up kits included:

For example, the original Asteroids game allowed skilled players to play indefinitely on a single credit. A speed-up kit made the game more challenging, thereby reducing playtime per credit and increasing revenue .

Some of the most famous examples of speed up kits are:

Speed-up kits were typically implemented through reverse engineering the original game and modifying it using:

While speed-up kits offered benefits to arcade operators, they raised legal and ethical questions:

The legal dispute between Atari and GCC over Super Missile Attack highlighted these concerns. The settlement resulted in GCC ceasing unauthorized modifications and instead developing licensed content resulting in Ms Pac Man 7.

Speed-up kits played a significant role in the arcade industry’s evolution:

MAME (Multiple Arcade Machine Emulator) is a free and open-source project that emulates the hardware of arcade systems, allowing classic games to run on modern platforms. Its primary goal is to preserve decades of software history by accurately documenting and replicating the behavior of original arcade hardware.

MAME version 0.1 was released on February 5, 1997, by Italian programmer Nicola Salmoria. This first version was a command-line application for MS-DOS and supported five games:

To run a game, you would use the DOS prompt like so:

mame pacman

All of the first games used a Z80 CPU, the first non-z80 game was Centipede which was released in version 0.10 on the 13th March 1997 8.

For a full release history of MAME check out: MAME Release Dates - Retro Arcade Guides

The first release of MAME32 occurred on July 18, 1997, with version 0.26.1 8. This marked the debut of a Windows-based version of MAME, featuring a graphical user interface (GUI) that simplified the process of loading and managing arcade ROMs.

Developed by Chris Kirmse, MAME32 made arcade emulation more accessible to a broader audience by eliminating the need for command-line operations required in the original MS-DOS version of MAME.

The Internet Arcade was first launched in early November 2014, it enables users to play classic arcade games directly in their web browser by leveraging JSMESS, a JavaScript port of the MAME emulator 9.

JSMESS was created by cross-compiling the original C/C++ codebase into JavaScript using Emscripten, a toolchain that translates C/C++ code into asm.js or WebAssembly for high-performance execution in browsers.

The original source code for JSMESS, is still available on JSMESS original Github. But please note that it has now been integrated into the main MAME repository, so this repository is now archived and no longer actively maintained, but the source remains accessible for historical and reference purposes.

For an up-to-date build of JSMESS you can follow the Emscripten part of the guide here: Compiling MAME — MAME Documentation 0.278 documentation

In 2015, MAME merged with MESS (Multi Emulator Super System), expanding its scope to include home consoles, computers, and calculators.

At CppCon 2016 Miodrag Milanović gave a fantastic talk about how MAME moved from C to modern C++, which helped with better compatibility, portability, and overall better code, you can watch it on youtube below:

MAME was first mentioned in issue 45 of EDGE magazine back in May 1997, only a few months after the first release, ever since then it has been mentioned in hundreds of magazines, books and newspapers.

It wasn’t just western media either, as far back as June 2000 MAME was being advertised in Japanese magazines (Arcadia Issue 1):

MAME was again featured in EDGE magazine in October 2002, where it was described as “by far the greatest and most important piece of video gaming code ever written”10.

Before Pong, There Was Computer Space - The MIT Press Reader ↩

Retro Gamer Issue 97 page 57 ↩

Inside Atari Games (“The One” Magazine 1990) and on http://www.atari-explorer.com/articles/articles-atari-games.html ↩ ↩2 ↩3

Retro Gamer Issue 28 ↩

mwenge/defender: Defender(1981) by Eugene Jarvis and Sam Dicker ↩ ↩2

Upgrade kits, lawsuits and Lite-Brite: How Ms. Pac-Man was made ↩ ↩2